Intro & Background

We’ve all been there, you arrive to a restaurant, early signs are promising. Dimly lit room, atmosphere seems good, you land the window seat with the nice view. Then you pick up the menu, and there’s 4 pages worth of reading, with countless options. The wine menu isn’t much better. Choice is great, but it’s all a little overwhelming, right?

You take a moment to scan the menu but find yourself in conversation immediately. The waiter comes to take the order, you need 5 more minutes. You haven’t even looked at the menu, which you do right away. All of a sudden, you’re back in conversation, waiter comes again 5 minutes later, you still haven’t read the menu.

Out of guilt, you devote your attention and effort to selecting your order, but you’re struggling. There’s too many options, you actually don’t take any of it in – ‘paralysis by analysis’. You suddenly feel the pressure and default back to the safe option – for me the steak. “But I told myself I wouldn’t have steak again?”.

What happened? In simple terms, my brain didn’t quite fancy the additional workload involved to work through the entire menu, so my subconscious took over an picked the steak. It’s never served me wrong right? This ‘paralysis by analysis’ happens to me quite often, I’m human. But every time it does, it reminds me. Our brains work hard enough, they don’t want to be worked any harder.

I see a lot of similarities in the way that manufacturers treat product packaging, with this cluttered menu design. The ‘whitespace’ of both the menu and product packaging are finite resources, and the unfortunate reality about humans and finite resources, is we use them all up, despite all evidence indicating to do the opposite.

As is the trend now, I asked ChatGPT to tell me the purpose of on-pack claims, which it returned “typically used to promote functional benefits, trigger emotional responses and provide opportunities for associations, build trust, or make comparisons with competitive offerings” – not bad, but it conveniently avoids any responsibility for moving the needle on buying behaviour?

The store aisle is one of the most competitive visual environments known to man, and this is where on-pack claims come into action. The aisle itself naturally creates cognitive load by the volume of products put before the consumer, forcing them to ‘bob and weave’ with their eyes, to find what they’re looking for. Granted, we have developed mechanisms to do this efficiently, but as a supplier or even retailer, the objective should be to minimise the load. Facilitate decisions, don’t motivate them.

At Future Proof, when we think of on-pack claims, aside from the regulatory obligations, the fundamental purpose is to compete within the aisle, differentiate and make consumers buy. After a first of its kind neuroscience study here in Ireland, testing over 100 products with diverse claims, the one thing that has consistently shown up across category, demographic and claim types was that Cognitive Load, or how hard we make shoppers work to process these messages, is a key factor in influencing buying behaviour.

When we scoped out this research originally, we wanted to focus on packaging in a broad and general sense. We initially selected 142 products, from both physical retail and eComm, across 12 diverse categories. Surprisingly, we found that 78% of all products we selected had at least one on-pack claim related to sustainability in some shape or form. With this level of prevalence, we then decided to focus in on sustainable claims, to understand three things; their impact on buying, how they perform against other types of claim types (Quality, Sourcing & Health Benefits) and finally within sustainability what are the most & least effective claim types. We excluded price & promotional claims from the research, as previous research established that these factors would have been major driving factors. Additionally, we are approaching this from an exclusion perspective, to identify poor performers.

1 – KEEP IT SIMPLE…

One of the key trends that emerged from testing, was that regardless of category, Cognitive Load, or how hard people needed to work to process the message, was a key factor in how the message affected purchasing. For every 1 unit increase in complexity, purchase intent, measured through a combination of neural data and stated responses, decreased by almost 9%.

What do I mean when I say Cognitive Load? In this context, it has two key drivers; the complexity of the message, or the complexity of the way it is presented visually. For example, claims like “No Palm Oil” spiked cognitive load, because many weren’t familiar with what it implied, and why it was a differentiator. Additionally, this high cognitive load is engaging, but too engaging because people were spending more time on Palm Oil and not thinking about the product or purchase decision. In comparison, claims like “Net Zero” or a Bord Bia Quality Mark for example, were much simpler to process.

The guidance here is that, in general terms, simpler claims work best. Aim for clear, straightforward messaging to enhance understanding, memorisation and engagement, which will ultimately increase the likelihood of affecting a purchase decision. Additionally, we found that higher cognitive loads are less effective at being encoded in our long-term memory, with a 1 unit increase in Cognitive Load negatively impacting memorisation by up to 13x. Basically resulting in weaker or even no association being formed between the message and the brand.

2 – ENGAGEMENT IS GOOD, OVER-ENGAGEMENT IS NOT SO GOOD

Engagement is a good thing, but manufacturers need to be careful that they do not create claims that are hyper-engaging as it comes at the cost of purchasing. The underlying logic here is that for high engagement claims, there was a negative correlation with buying decisions. While it is important that package claims are engaging, this should not come at the cost of the product or brand. The advice here is to always include a mechanism of guiding towards a purchase decision or brand impact. Sustainability can often fall into this trap, being highly engaging in its general sense, meaning people get very interested in the purpose dimension, but not in the product.

3 – MAKE YOUR CLAIMS EMOTIONALLY RELEVANT

Claims that trigger emotional responses, are generally speaking, more effective at encoding memories, whilst also generating increased desire and purchase intent within consumers. The data showed that emotion is positively correlated with desire and influenced by cognitive load. Emotional resonance to the different product presentations not only aids in memory encoding but also amplifies desire and could influence buying decisions.

To summarise, the topline guidance here is to consider the balancing act between the brand, product and the on-package claim or message. The crucial element is to understand how these interact, while keeping it simple, engaging and emotionally stimulating, all while remaining relevant to the product and brand.

HOW DOES SUSTAINABILITY ON-PACK MEASURE UP AGAINST THE REST?

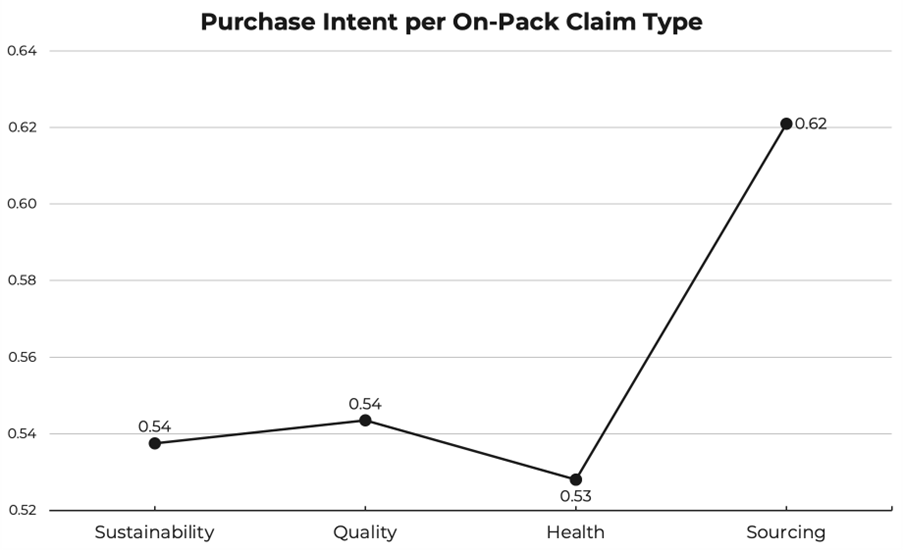

As mentioned, sustainability claims are littered across almost all packages at the moment, and with good reason due to its obvious importance. But, we set out to understand and quantify how effective these sustainability claims were at affecting buying behaviours. And so, we compared them to different claim types like Quality, Health & Sourcing Claims. What did we find?

- On-pack claims related to product sourcing were generally 8-9% more effective than all other categories – sustainability, quality or health benefit claims

- Generally speaking, claims about product quality and health benefits were largely in-line with the results of Sustainability without any significant differences.

- Interestingly though, we found that there was a much higher degree of variability in the other three categories compared to sustainability, which suggests people process sustainability in a more uniform way, compared to the other claim types.

Considering this variability, we needed to dig a little deeper. We had already established that Cognitive Load played a significant role in Buying Behaviours, as a result we decided to split out the packaging claims in each category into those that generated a high and low cognitive load.

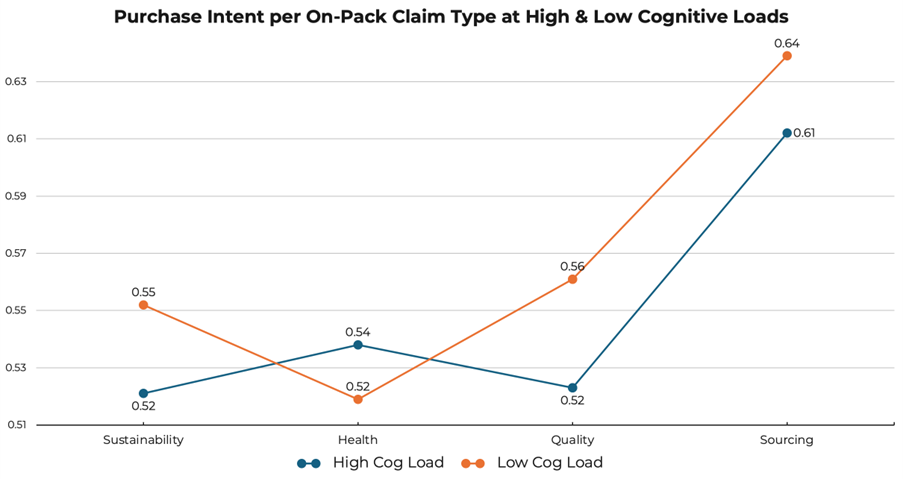

When making claims about Sustainability and Product Quality, we see a notable uplift in performance for claims that generate lower cognitive loads. The guidance from this is to always aim for clear and direct messaging to enhance audience understanding and engagement. Additionally, it was shown that simplicity drove higher memorisation. When memorability is important, make sure to keep it simple.

One of the more interesting findings, which contradicts what we are saying about cognitive load was in the Health Claims space. Higher cognitive loads and evaluations typically evoke stronger emotional responses when it comes to health. Messages that are thought-provoking to process, without being not overly complex seem to maintain emotional resonance. In this context, balance complexity as there is a higher degree of consideration for personal health.

Sourcing as seen in the chart was the best performing category, regardless of complexity or cognitive load. However, given the association of cognitive load with purchase intent, aim to strike a balance in presenting sourcing information. It works best when it carries an intrinsic message or a broader meaning, but is simple enough to be processed instantly.

THEN WHAT ARE THE MOST EFFECTIVE TYPES OF CLAIMS WITHIN SUSTAINABILITY?

The objective was to evaluate the impact of different groups of sustainability claims, and find out what some of the most optimal claim types are.

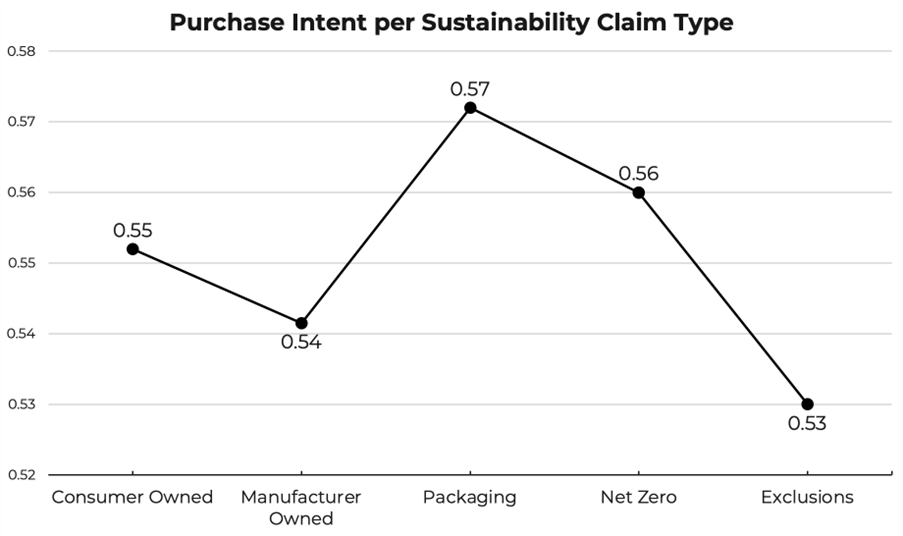

We grouped them into 5 categories, 1- Consumer Owned Actions where products are sustainable and consumers have the ability to recycle / upcycle the product (“100% Recyclable”), 2- Manufacturer Owned Actions where sustainability has been baked into the supply chain (“Made from 100% Recycled Plastic”), 3- Packaging Claims, where the claim is specific related to the packaging in which the product resides, 4- Net Zero Claims, where claims fall under the Net Zero umbrella, 5- Exclusions, where the claim suggests by omitting a certain ingredient or material, the product is aligning with the sustainability agenda.

IN GENERAL, ALL SUSTAINABILITY CLAIMS WORK VERY SIMILARLY – BUT THIS ISN’T THE WAY WE PROCESS THEM

Unfortunately, when we look at Sustainability as a whole, we didn’t really find any significant differences. In general terms, and it could be argued that there are no real standout claims under the sustainability umbrella. When we split data out by gender, demographic or categories, we still saw the same trend, which was particularly interesting.

This actually raises is more questions than it answers. But it was important to do a little more digging because looking at these claims in a general sense doesn’t actually reflect the way we process these messages, and when we go another level deeper into the mechanics behind how we process the messages, we start to find some interesting insights.

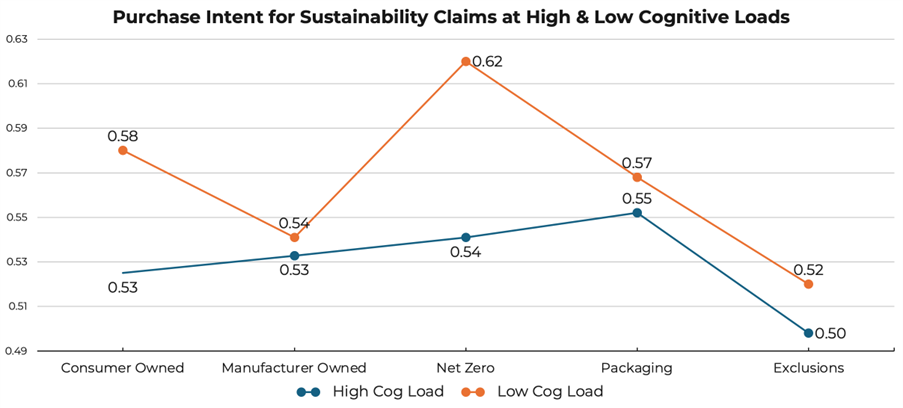

So we turned back to cognitive load, which we knew already was an important factor. After splitting out each of the claim categories by high and low cognitive load, we can see significant differences in performance.

Simpler Sustainability Claims Facilitate Purchasing in the Brain. Across all message types we see that the more simple claims, that do not create cognitive load for the buyer outperform complexity across all claim types.

Claiming a product was produced from recycled materials doesn’t motivate like telling people they can recycle. We can see that consumer owned actions with a low cognitive load like “100% Recyclable” outperforms Manufacturer Owned Claims like “Made from 100% Recycled Plastics”. This actually contradicts our entry hypothesis, where we thought claims that were baked into the supply chain and do not require any action from the consumer would be more effective. But this does suggest that despite what people state consciously, subconsciously there is a slightly aversive nature to recycled products, potentially because of negative associations of things perceived to be ‘second hand’. This aspect of the sustainability challenge, creates huge challenges in closing the Say-Do gap. On the flip side of this dynamic, it appears as though providing the opportunity for consumers to be virtuous and do their bit for the environment, seems to be a stronger approach, provided the message is delivered efficiently. Our current thoughts are that this facilitates buying, but there is no evidence to suggest this would motivate the subsequent recycling action.

Carbon Net Zero claims are the strongest performer within sustainability, and as with all categories there is a rise in performance when it was easier to process and comprehend, however the difference is most pronounced in the area of Net Zero claims. It appears that Net Zero claims, work similarly generally benefit The logic behind this is similar to the sourcing point above, net zero claims are simple at a surface level but carry a lot of implied messaging without taxing the brain.

Exclusions – particularly complex ones very poor performers. Claims like “No Palm Oil need people to work to process, as Palm Oil claims are not as mainstream as things like Net Zero. However, if a brand does decide to go down the exclusion route, the recommendation here, again, is to make sure that the message or information is easy to process, and where possible, aim to build in a broader message.